At the end of last year I attended Africa Oil Week where Madagascar were due to announce a new licensing round. 2018 was quite a busy year for licensing in Africa where many countries are still largely under-explored. Frontier exploration virtually stopped during the downturn, but it is back on the agenda as companies look to boost reserves.

Frontier exploration projects often start with a data gathering phase, with companies reporting that this typically takes up around a third of the total project time. Maps are a great way to get a spatial understanding of available data.

Common data sources might include:

- A corporate geoscience database or an interpretation project with pre-loaded data

- GIS and cultural information from a range of providers

- Legacy data including flat files and images

A few observations:

- Retain a healthy degree of scepticism about all your data

While data QA has vastly improved over the years, never assume that everything in your database is correct. As an example, I came across a suite of QC’d well logs some years ago where I had a sense of déjà vu. On further investigation, it turned out there was a 600m section of logs which was exactly the same as the 600m above it! It looked like the loggers had lost a lot of data and literally copied and pasted a section. When the well was drilled, the bogus section was much shallower than the target formation, so no-one had noticed or cared. However, for the study we were working on it was of interest and we had to discount this well completely. The vast majority of data in your databases will be reliable, but just keep in mind that something may not be.

- Be cautious about the accuracy of georeferenced and digitised data

Historic maps can be a great source of information helping to reduce data acquisition costs and giving an early insight into the geology of new acreage. Typically, they’ll be scanned, georeferenced and contours, faults etc. will be digitised. Aside from digitising tolerance errors, consider whether the original map had full information about its coordinate reference system. If not, then the coordinate system assigned is a best guess.

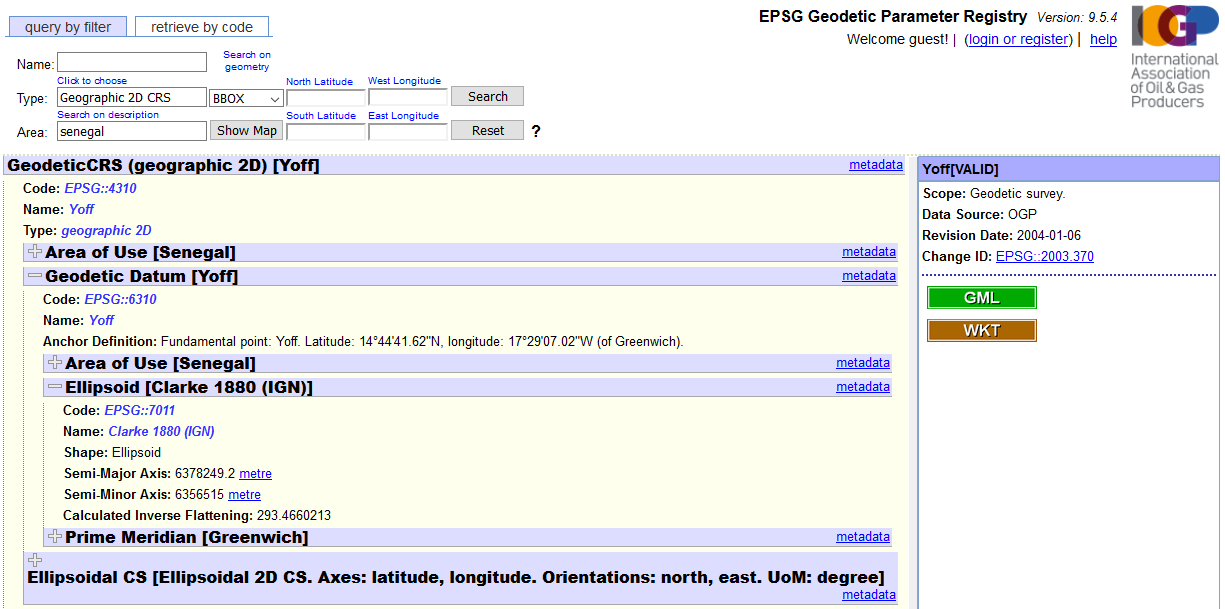

A great source of coordinate system definitions is the EPSG database which was created and is maintained by a group of oil industry surveyors. It’s available online through the EPSG Geodetic Parameter Registry (Fig 1, below) which includes several search tools including the ability to search by area. This option will return a list of coordinate systems that is appropriate for the selected region. If you’re unsure about coordinate systems, and don’t have access to a surveyor or geodesist, this is a good starting point.

Figure 1: The EPSG Parameter Registry – an invaluable free on-line resource for coordinate system information

Even without a full coordinate system, there may be fragments of coordinate system related meta-data that can help to eliminate some of the options. Be particularly careful with geodetic datums (strictly speaking “geographic coordinate systems”) as getting this wrong can move data by hundreds of metres.

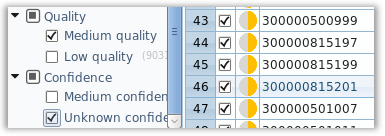

Digitised data from georeferenced maps can save a lot of time and money, but you do need to consider potential for error. For basin level exploration, this may be acceptable, however it wouldn’t be a good idea to plan a well near a digitised fault. If possible, record meta-data and a quality metric (figure 2) with any data digitised from legacy maps. If you don’t, then it may become impossible for other to distinguish between it and accurate, interpreted data which could lead to very expensive mistakes in future.

Figure 2: Metadata and quality metrics give data longevity and add value

- Don’t ignore any data and map it directly from source

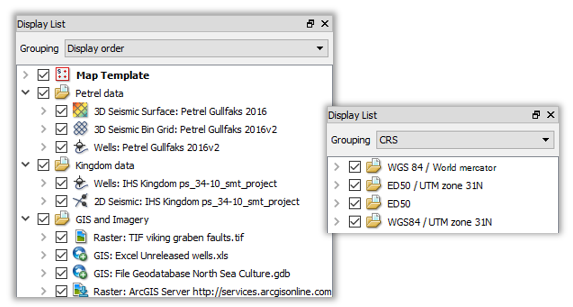

When building your map, try and find an application that accesses data directly from source (figure 3), particularly if coordinate conversion is required. Each time data is coordinate converted, a small error is introduced. An export, convert, import workflow increases the chances of mistakes, as well as resulting in duplication. Keeping data in its source coordinate system and dynamically converting it to the preferred map coordinate system will help keep your data accurate and give you confidence in your frontier exploration maps.

Figure 3: Access data directly and keep the original coordinate system if possible

If you come across data in a difficult format, don’t just ignore it. There are a range of mapping tools which handle a wide range of formats and might just offer an easy solution. You never know if it will reveal an important insight.

In summary, frontier mapping can be great fun and it requires detective work and leaves a lot of leeway for interpretation. Like a good detective, look for as many clues as possible, don’t ignore any evidence, be critical of the information you reveal, and be open minded. This will give you the best chance of building a credible data-set and making sound decisions going forward.